In May 1994, this article was published in Indianapolis Monthly Magazine. For many years, I’ve had an online version of this article on my website with a label that said “A shorter version of this article appeared in the May 1994 issue of “Indianapolis Monthly” magazine. This is the story as originally written.”

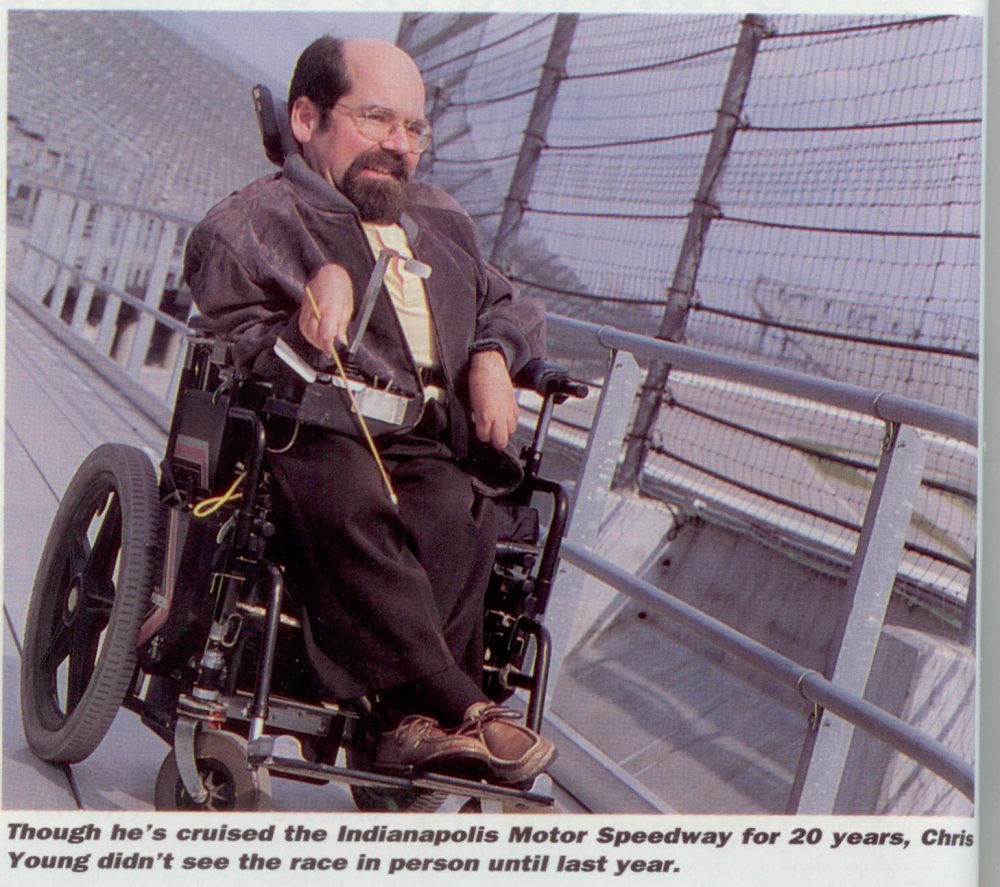

The published story had only one photograph of me sitting at the track. That photograph was taken on a cold day in March by a staff photographer for the magazine. The online version contained that photograph and a bunch of other photos my mom had taken as well as some other old photographs of me at age 6 at my first visit to the Indianapolis Note or Speedway.

In June 2021, while preparing for a blog post in my Author’s Journal series, I decided to dig out the original article and put up the published version of the story. Upon rereading both versions I was a bit shocked by the differences. The online version must’ve been an early draft and not the version that I ultimately submitted to the magazine. Some of the writing in that online version was terrible and the rewrites in the published version sounded like something I had written. I can’t believe that some of the rewritten material was rewritten by the editor.

Click here to read the older online version with more photos.

This page contains a reasonably faithful representation of what the article looked like in the magazine. The sidebar quotes inserted in the text I had a slightly different place but other than that, the print version looks a lot like this. The heading “First Person” means it was part of a recurring feature of first-person articles in the magazine. A trend that I started with my award-winning 1987 article “The Reunion”.

FIRST PERSON

Being There

by Chris Young

500 fan finally sees his

first race.

Getting to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was always half the hassle for computer consultant and race fan Chris Young. But though confined to a wheelchair since childhood by muscular dystrophy, he still made pottery around the track during May a yearly tradition, last year realized his life long dream of attending the race in person. This is his story.

I lived in Indianapolis all of my 38 years – past 35 less than a mile from turn four of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Yet, though my family and I always been race fans and I made regular visits to the track during May, I always spent Memorial Day listening to the race on the radio. More than 400,000 other people watch the event in person with no complaints, so why was I so picky? I’m not –I’m handicapped.

My lifelong battle with muscular dystrophy and the lack of mobility it forced upon kept me from seeing my first race until 1993. That’s because throughout most of my career as a fan, the Speedway offered only two poor options for wheelchair seating: infield grass areas (complete with drunks and near-naked women) or the wooden bleachers on the inside main straight, north of the Tower Terrace. While this was acceptable for practice or qualifying, a wheelchair on a very now walkway with a full race day crowd would have been a dangerous obstruction.

The situation improved about five years ago when the Terrence Extension was replaced with a grandstand topped with suites and a new wheelchair section installed inside the track just before turn two. But this facility, though one of the finest I’ve ever seen, offers a very limited view that’s further diminished by my handicap, which keeps me from turning my head very far to the left or right. On less crowded practice or qualifying days I can take up two spaces and turn my entire wheelchair to get a better view, but on race day it would mean purchasing two seats just for myself.

In spite of the difficulties, when the Speedway announced it will host the Brickyard 400, I could no longer resist the urge to see a race in person. I decided to take my chances in the wheelchair area – an iffy proposition, since I didn’t order tickets until early May 1993, long after I figured all the slots had sold out.

After sending in my request, I resumed my usual race month routine, spending every spare moment tooling around the track. Because I work at home as a computer consultant and writer, I can take plenty of time off to feed my need to be near-wheelchairs called Indy cars.

I spent most of my days at the track cruising Gasoline Alley in my motorized wheelchair, I’m quite recognizable as the guy with the bald head, beard in the video camera mounted on his chair (I’m told my 20 years of cruising the garages have made me a fixture there). Gasoline Alley holds such a strong appeal because I enjoy being close to the crews who tinker with millions of dollars’ worth of equipment.

When the Speedway

announced it would

host the Brickyard

400, I could no longer

resist the urge to see

a race in person.

# # #

I’m also a bit of a tinkerer, though on a much smaller scale. One year, for instance, I spent $80 on an electric stopwatch, gambling that I could adapt it for my use. My dad disassembled it and, under my direction, soldered on new, easy-to-use buttons that I could work myself. But the biggest such gamble was the $700 video camera that we adapted to my chair with new controls and a feather balance camera mount. That the gadgetry caught the attention of chief mechanic Peter Parrot one year as he worked on Rick Mears’s car in the Penske garage. When he complimented me on the clever job I’d done, I told him, “I just like buying high-tech toys and then betting that I can make them do what I want them to do.”

“Hmmm, that sounds like my job description,” he said. But in my case it’s Roger (Penske) who loses money when.”

Perhaps Gasoline Alley was such fun for me because it is the home of high-tech tinkerers like Team Penske. Roger is the most determined and competitive man in racing today, and if I have a favorite driver in any year, he’s probably a Penske employee. With drivers like Mark Donahue, Mario Andretti, Danny Sullivan, Rick Mears, Emerson Fittipaldi and now Paul Tracy, Penske has shown that the smartest drivers and the newest cars win races.

Unfortunately, it seemed that my garage fun was about to end. My muscular dystrophy leaves me a tiny bit weaker every year, and it taxes me to the limit when I maneuver my wheelchair over bumpy pavement, in a crowd and in the hot sun or cold wind while trying to operate a video camera. I needed to prepare myself for the possibility that I might spend 1993 in the handicapped section just watching, which meant I needed a new high-tech toy to play with in the grandstand.

A scanner radio for monitoring conversations between the crews and drivers proved the perfect solution. After doing some research I discovered that the Frequency Fan Club offers an excellent deal on a 200-channel 800 MHz model and also those in a subscription to their newsletter containing up-to-date lists of frequencies. Other information on where to tune and what to listen for can be found on CompuServe’s Racing Information Service. I ordered my radio a bit late and didn’t receive it until the end of the first week of practice, given me time to try the video in the garage area one more time.

The first week of May, my mother went over to the Speedway to pick up our season gate passes and garage badges. Mom is awesome a great race fan and enjoys sitting in the stands watching cars while I’m in the garages. At the ticket counter she asked what seemed like a silly question: “You wouldn’t have any leftover handicapped this year, would you?” It’s common knowledge that the race sells out months in advance, so we were amazed when the ticket agent said, ”Yes, how many do you need?”

We owed our good fortune to the fact that a new grandstand with a wheelchair seating area had been completed in time for use in 1993, but too late to be listed on the ticket order forms. All sales had been over-the-counter and by word-of-mouth.

This dream-come-true was even better than I had imagined, because the new wheelchair seats, called the North Vista Wheelchair Platform, run all the way from turn three to turn four on the outside the track, offering a better view for my limited head movement than the wheelchair area inside the south chute.

We came back the next day with the necessary cash to buy one wheelchair seat and two companion seats for Mom and Dad to go with me. I also participated in the word-of-mouth publicity campaign, enabling wheelchair-bound cousin Nancy to pick up the last three available tickets.

Family commitments kept me from the first two days of practice, but on May 10, I was there, full of anticipation and excitement. Mom always sits in the stands just south of the garage entrance, so I know where to find her if I need her. I spend most days touring the garages, with the month-long goal of getting one good video shot of every car that qualifies. We check in with each other about once every hour and then head home about 4 or 5 p.m., depending on tired and sunburnt we are.

That first day was a disappointing mess. My tour of the garages went well, but a minor problem with the camera left me with no video. At the designated time I went to meet Mom, but seemed to have more difficulty than usual driving over the bumpy asphalt behind the grandstand. Finally, I made it to the right spot, and Mom arrived with a Coke for me. We diagnosed and fixed the camera problem and I took off again for the garages.

But no sooner was Mom out of sight than I hit a bump too hard and slumped forward. My hand slipped off the wheelchair control and I was stuck – the start of a truly phenomenal run of bad luck forced me to call on the help of three different Good Samaritans that day. I gave up and returned to my meeting spot behind the stands. When Mom showed up, I told her what happened and I decided I wanted to go home.

Monday evening found me sitting at home in silent frustration. It seemed I no longer had the ability to get around on my own in a hostile environment. After a suitable amount of sulking I entertained a new strategy: perhaps converting my wheelchair from hand to mouth controls, a step I wanted I wanted to delay until I lost all use of my arms. Still, it was the bumpy pavement that was my downfall, and Gasoline Alley itself had smooth concrete. If I could get in and out of the garage area, I was sure I’d be back in business.

I spent the last

practice days taking

pictures, monitoring

the radio and counting

the minutes until the

race.

# # #

After some discussions with Mom, we changed our plan of attack, on Tuesday she escorted me into Gasoline Alley left and left me on the smooth pavement. The new arrangement worked beautifully, and in the following days I shot some great video and enjoyed every minute of it.

Late in the first week of practice my new scanner radio arrived. Some days I spent more time in the wheelchair area watching cars while listening to the radio than I did shooting video in the garage. I spent the last days of practice taking pictures, monitoring the radio and counting the minutes until the race. The night before the big day I felt like a kid on Christmas Eve. Somehow I managed to sleep a reasonable number of hours. When I woke up I joked with my parents, “Did Santa come last night and make it become race day?”

It didn’t take long to pack everything in the van. Give my mom a month to plan for an event and she’ll gather in left supplies to invade a small country. Dad shook his head in amazement. “Gee, the race only lasts three hours. This looks like a week’s vacation!”

“If we spend all day in the van waiting on the rain, you’ll be glad I brought this stuff,” Mom replied.

Considering that some folks spend hours in traffic jams trying to get to the race, it seemed almost sinful that we took only 10 minutes. Thanks to a special window sticker given to all handicapped ticket buyers, we drove right by the long lines trying to park in the Coke plant lot to a reserved area near the grandstand.

We parked close to our assigned seats in Section 22, very near the entrance to the fourth turn. Upon reaching the grandstand we encountered a well-designed wheelchair ramp with level places every 30 feet to allow for rest breaks. We presented our tickets to the patrolman, and he pointed to a spot right in front of the ramp We were finally there!

But my heart sank when I saw where “there” was. The wheelchair seat was at the front of the platform up against the railing, placing the concrete retaining wall and steel fence only about 10 feet in front of me. I had no idea that I would be so incredibly close, and I nearly cried at the thought of spending the next three hours staring stiffnecked at a few feet of track.

Dad pushed my chair into the right space assigned to me, and I tried looking to my right. My head barely moves that way, so I could see but a few feet into the turn. Then I turned my head left, and before me stretched a breathtaking view of the last half of the third turn all of the short straight, and the entrance of turn four.

The location was perfect, the view was perfect, the weather was perfect and I was perfectly ready to see my first live, in-person Indy 500. All of the traditional prerace festivities began at 10 a.m. as Mom helped me jot down some last-scanner frequencies broadcast by the Frequency Fan Club. A parade of sororities drove by in pace cars and waved. I had a great, fence-hugging view of them.

From the sounds of Taps to a roaring F-16 fly-by to Back Home Again in Indiana to “Lady and gentlemen, start your engines,” the festivities continued. Soon the parade lap, led by three pace cars, rolled into view out of turn three and headed toward me. As the cars rolled by, a stiff breeze blew a wave of exhaust in my face. I chuckled to myself as I recalled Robert Duval in Apocalypse Now, thinking of the methanol fumes smelled like victory.

The next sight was a lone pace car speeding out of turn three, followed by the near-perfect rows of three abreast lead by Arie Luyendyk, Mario Andretti and Raul Boesel. The field rocketed by, and Tom Carnegie announced that the green flag was out. The race was on!

Boesel appeared in the lead as the field came toward us from turn three, prompting a large contingent of Brazilian fans in the stands behind me to cheer and chant their approval. Over the first few laps is a lead widened until Jim Crawford drove by in the warm-up (or is it slow down?) lane in turn four. Smoke trailed from his car, and moments later the wind delivered a new scent.

As I listened to Frenchman Stephan Gregoire speaking his native tongue on the scanner, I wished I had studied harder in high school and college French class. My D+ average was of no use to me today.

A few laps into the race I saw a large puff of white smoke erupt from a dark blue car as it bounced off the outside wall just out of turn three. Although I have seen cars spit out before, I had never seen an actual impact in person. As the car rolled by me with a badly mangled right front suspension, I could see it was Danny Sullivan. He rolled to a stop too far into turn four for my stiff neck, but mom reported he had climbed out. She snapped a photo as safety vehicles towed the car away.

I knew one race fan who was ecstatic when Mario Andretti took the lead shortly thereafter. My cousin Nancy was sitting about eight wheelchair seats to my left and cheered her hero as she witnessed her first 500. Nancy has been a lifelong fan and, like me, spends what time she can at the track. Mario has been quite kind to her over the years, knowing what a devoted supporter she is, and always takes time to give her a hug and a kiss and they pose for a picture.

It seemed that the race had just started when I noticed the halfway point had already passed. The quiet moments when the field was on the far end of the track moving slowly under caution, offered time to relax, talk and grab a bite of lunch. Lap after lap under green is an assault on one’s senses when sitting that close to the action, where the noise is felt as much as heard. I noticed a fine layer of grit accumulating on my skin, my eyeglasses were getting dirty, and I had a strange oily taste in my mouth. I wasn’t just seeing the race – I was immersed in it.

The radio was abuzz with the strategy for the final pit stops. Nigel Mansell led, with Emerson Fittipaldi in second place and Arie right behind. I heard the Penske crew warn Emmo to watch for Arie on the restart. I should have known something was up Emmo’s sleeve. The green flashed on, and an unaware Mansell had dropped to third place by the time he reached the first turn.

While hundreds of thousands cheered Emmo, Aerie and Nigel on board, I sat in shock as I heard USAC reports that all three had passed under the yellow. I couldn’t believe that a last-minute stop-and-go penalty might hand the race to Boesel, who was in fourth place. As I waited for the word on penalties, the radio blared with a familiar British voice saying, “I’ve hit the wall in turn two!” It was obviously Mansell, who somehow continued on to finish third. The penalties to the leaders never materialized and Emerson Fittipaldi earned his second 500 victory. Arie finished second, with Mansell and Boesel not far behind.

I noticed a fine layer

of grit on my skin and

I had an oily taste in

my mouth. I wasn’t

just seeing the race –

I was immersed in it.

# # #

My hero, the high-tech tinkerer and car owner Roger Penske, had won3g his ninth Indy 500 in 25 years. The Brazilian contingent behind me saying and cheered their approval as their countrymen Fittipaldi took a victory lap. I was hot, dirty, tired and fulfilled. It was an experience I’ll never forget.

Upon arriving home, I joined on my computer and began composing this reflection. As I wrote through the next day, pausing only to fill out my application for tickets to next year’s race, I began to understand why I’m a race fan. It’s more than affection for technology or the thrill of speed or the quest for victory. It’s the struggle itself that appeals to me.

My month of May had its ups and downs, but in the end my best efforts and grace of God made it a wonderful experience – something akin to what the drivers must feel. After all, life isn’t about winning; it’s about racing. It’s about doing your best against early odds and discovering the rewards 3oOf participation itself. It’s about bouncing back when things go wrong and constantly growing, no matter how much you have already accomplished.

That’s why I’m a race fan.